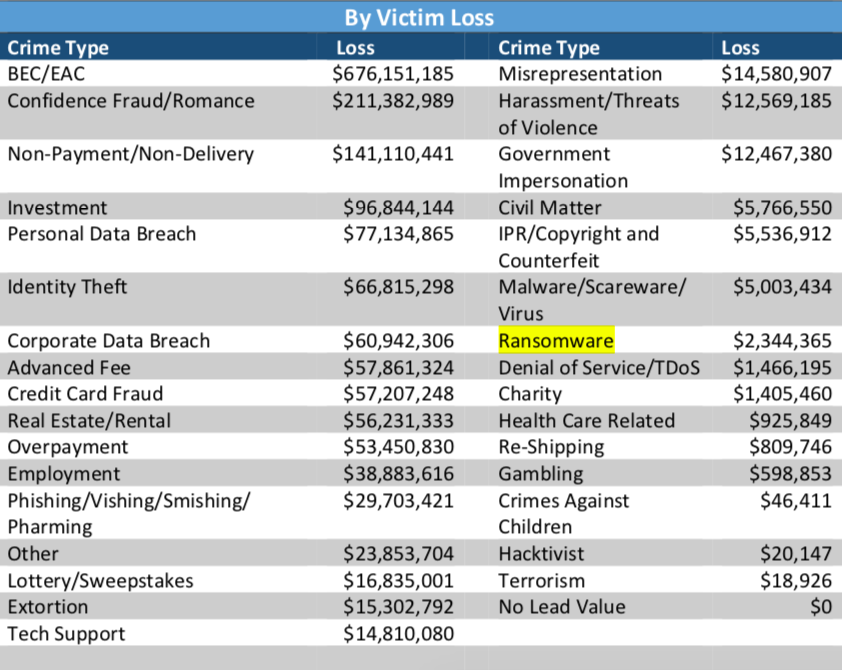

Ransomware has been a prominent threat to enterprises, SMBs, and individuals alike since the mid-2000s. In 2017, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) received 1,783 ransomware complaints that cost victims over $2.3 million. Those complaints, however, represent only the attacks reported to IC3. The actual number of ransomware attacks and costs are much higher. In fact, there were an estimated 184 million ransomware attacks last year alone. Ransomware was originally intended to target individuals, who still comprise the majority of attacks today.

Image via 2017 Internet Crime Report.

In this article, we examine the history of ransomware from its first documented attack in 1989 to the present day. We discuss in detail some of the most significant ransomware attacks and variants. Finally, we take a look at where ransomware is headed in 2018 and beyond.

Table of Contents:

- What is Ransomware?

- How Ransomware Attacks Work

- The First Ransomware Attack

- The Evolution of Ransomware

- The Biggest Ransomware Attacks and Most Prominent Variants

- The Future of Ransomware

- Protecting Against Ransomware Attacks

- Further Reading on Ransomware and Ransomware Attacks

What is Ransomware?

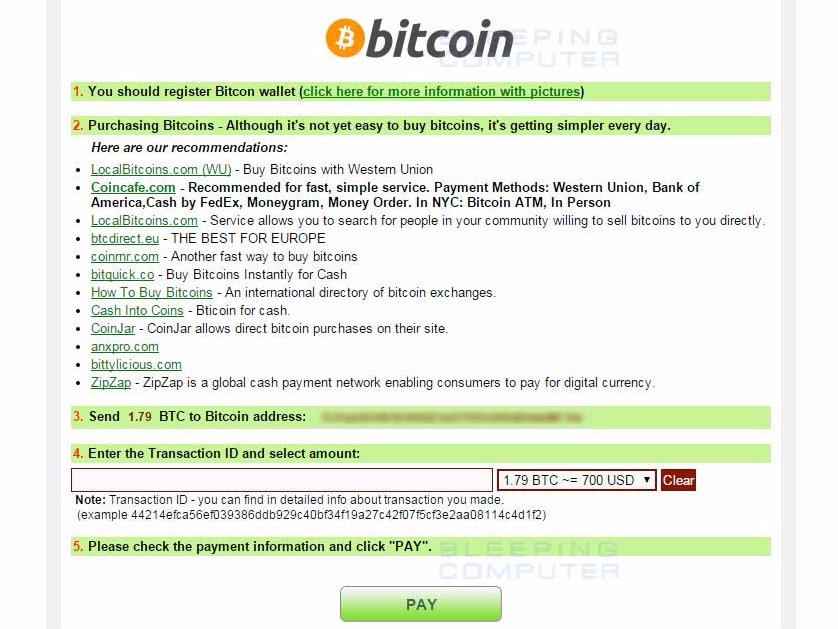

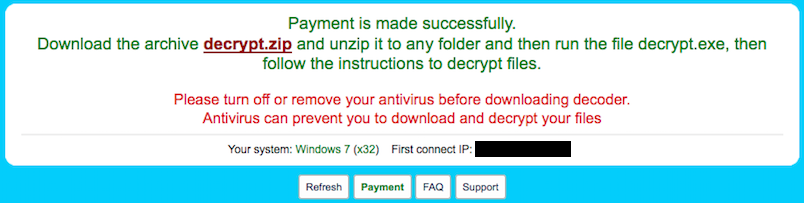

Ransomware is a type of malicious software that gains access to files or systems and blocks user access to those files or systems. Then, all files, or even entire devices, are held hostage using encryption until the victim pays a ransom in exchange for a decryption key. The key allows the user to access the files or systems encrypted by the program.

A CryptoWall 4 website provides instructions for purchasing bitcoins to pay ransoms. Screenshot via Business Insider.

While ransomware has been around for decades, ransomware varieties have grown increasingly advanced in their capabilities for spreading, evading detection, encrypting files, and coercing users into paying ransoms. “New-age ransomware involves a combination of advanced distribution efforts such as pre-built infrastructures used to easily and widely distribute new varieties as well as advanced development techniques such as using crypters to ensure reverse-engineering is extremely difficult,” explains Ryan Francis, managing editor of CSO and Network World. “Additionally, the use of offline encryption methods are becoming popular in which ransomware takes advantage of legitimate system features such as Microsoft’s CryptoAPI, eliminating the need for Command and Control (C2) communications.”

A CryptoWall website displays decryption instructions after a victim paid a ransom of over $500. Screenshot via Business Insider.

With ransomware holding steady as one of the most significant threats facing businesses and individuals today, it is no surprise that attacks are becoming increasingly sophisticated, more challenging to prevent, and more damaging to their victims.

How Ransomware Attacks Work

Now that we have a loose definition of ransomware, let us go over a more detailed account of how these malicious programs gain access to a company’s files and systems. The term “ransomware” describes the function of the software, which is to extort users or businesses for financial gain. However, the program has to gain access to the files or system that it will hold ransom. This access happens through infection or attack vectors.

Malware and virus software share similarities to biological illnesses. Due to those similarities, deemed entry points are often called “vectors,” much like the world of epidemiology uses the term for carriers of harmful pathogens. Like the biological world, there are a number of ways for systems to be corrupted and subsequently ransomed. Technically, an attack or infection vector is the means by which ransomware obtains access.

Examples of vector types include:

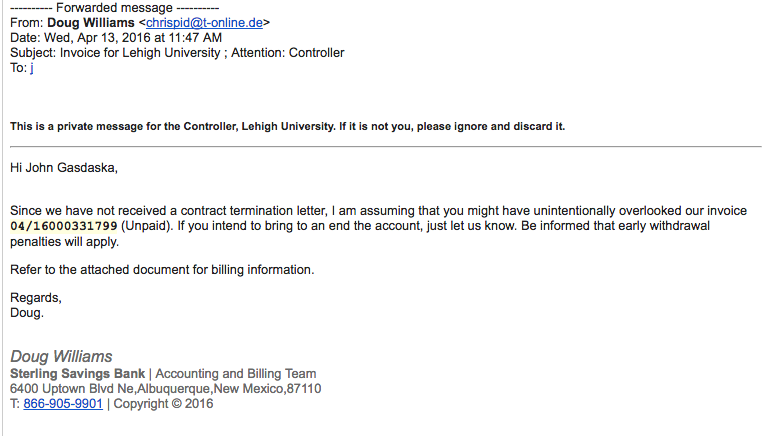

Email Attachments

Screenshot via EDTS.

A common method of deception used to distribute ransomware is the sending of a compelling reason for businesses to open malware disguised as an urgent email attachment. If an invoice comes to a business owner or to the accounts payable department, it is likely to be opened. This tactic, like many related in this list, engages in deception to gain access to files and/or systems.

Messages

Screenshot via The Windows Club.

Another means of deception employed by ransomware assailants is to message victims on social media. One of most prominent channels used in this approach is Facebook Messenger. Accounts that mimic a user’s current “friends” are created. Those accounts are used to send messages with file attachments. Once opened, ransomware could gain access to and lock down networks connected to the infected device.

Pop-Ups

Screenshot via Fixyourbrowser.

Another common, yet older, ransomware vector is the online “pop-ups.” Pop-ups are made to mimic currently-used software so that users will feel more comfortable following prompts, which are ultimately designed to hurt the user.

The First Ransomware Attack

While ransomware has maintained prominence as one of the biggest threats since 2005, the first attacks occurred much earlier. According to Becker’s Hospital Review, the first known ransomware attack occurred in 1989 and targeted the healthcare industry. 28 years later, the healthcare industry remains a top target for ransomware attacks.

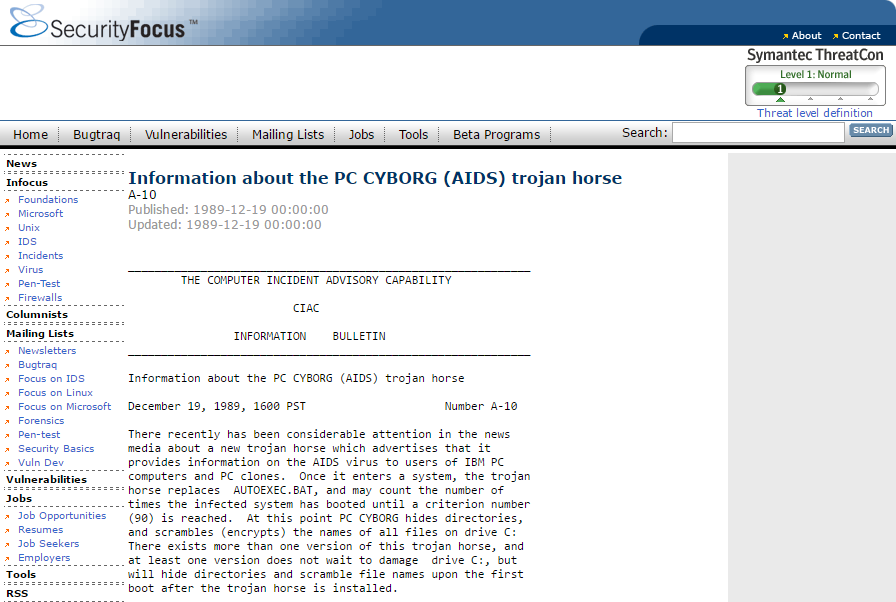

PC CYBORG advisory from 1989. Screenshot originally taken from Security Focus.

The first known attack was initiated in 1989 by Joseph Popp, PhD, an AIDS researcher, who carried out the attack by distributing 20,000 floppy disks to AIDS researchers spanning more than 90 countries, claiming that the disks contained a program that analyzed an individual’s risk of acquiring AIDS through the use of a questionnaire. However, the disk also contained a malware program that initially remained dormant in computers, only activating after a computer was powered on 90 times. After the 90-start threshold was reached, the malware displayed a message demanding a payment of $189 and another $378 for a software lease. This ransomware attack became known as the AIDS Trojan, or the PC Cyborg.

The Evolution of Ransomware

Of course, this first ransomware attack was rudimentary at best and reports indicate that it had flaws, but it did set the stage for the evolution of ransomware into the sophisticated attacks carried out today.

Early ransomware developers typically wrote their own encryption code, according to an article in Fast Company. Today’s attackers are increasingly reliant on, “off-the-shelf libraries that are significantly harder to crack,” and are leveraging more sophisticated methods of delivery such as spear-phishing campaigns rather than the traditional phishing email blasts, which are frequently filtered out by email spam filters today.

Some sophisticated attackers are developing toolkits that can be downloaded and deployed by attackers with less technical skills. Some of the most advanced cybercriminals are monetizing ransomware by offering ransomware-as-a-service programs, which has led to the rise in prominence of well-known ransomware like CryptoLocker, CryptoWall, Locky, and TeslaCrypt. These are some examples of common types of advanced malware. CryptoWall alone has generated more than $320 million in revenue.

After the first documented ransomware attack in 1989, this type of cybercrime remained uncommon until the mid-2000s, when attacks began utilizing more sophisticated and tougher-to-crack encryption algorithms such as RSA encryption. Popular during this time were Gpcode, TROJ.RANSOM.A, Archiveus, Krotten, Cryzip, and MayArchive. In 2011, a ransomware worm emerged that imitated the Windows Product Activation notice, making it more difficult for users to tell the difference between genuine notifications and threats.

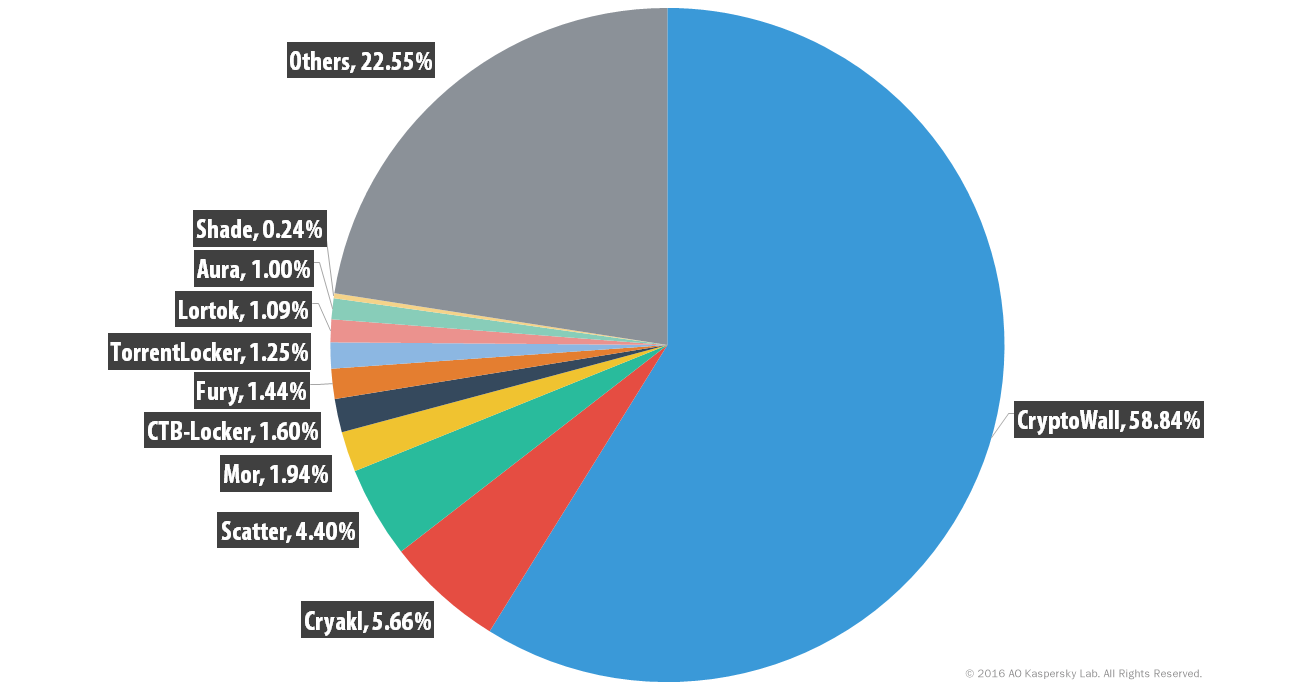

Percentage distribution of ransomware variants observed by Kaspersky Labs, 2014-2015. Image originally taken from SecureList.

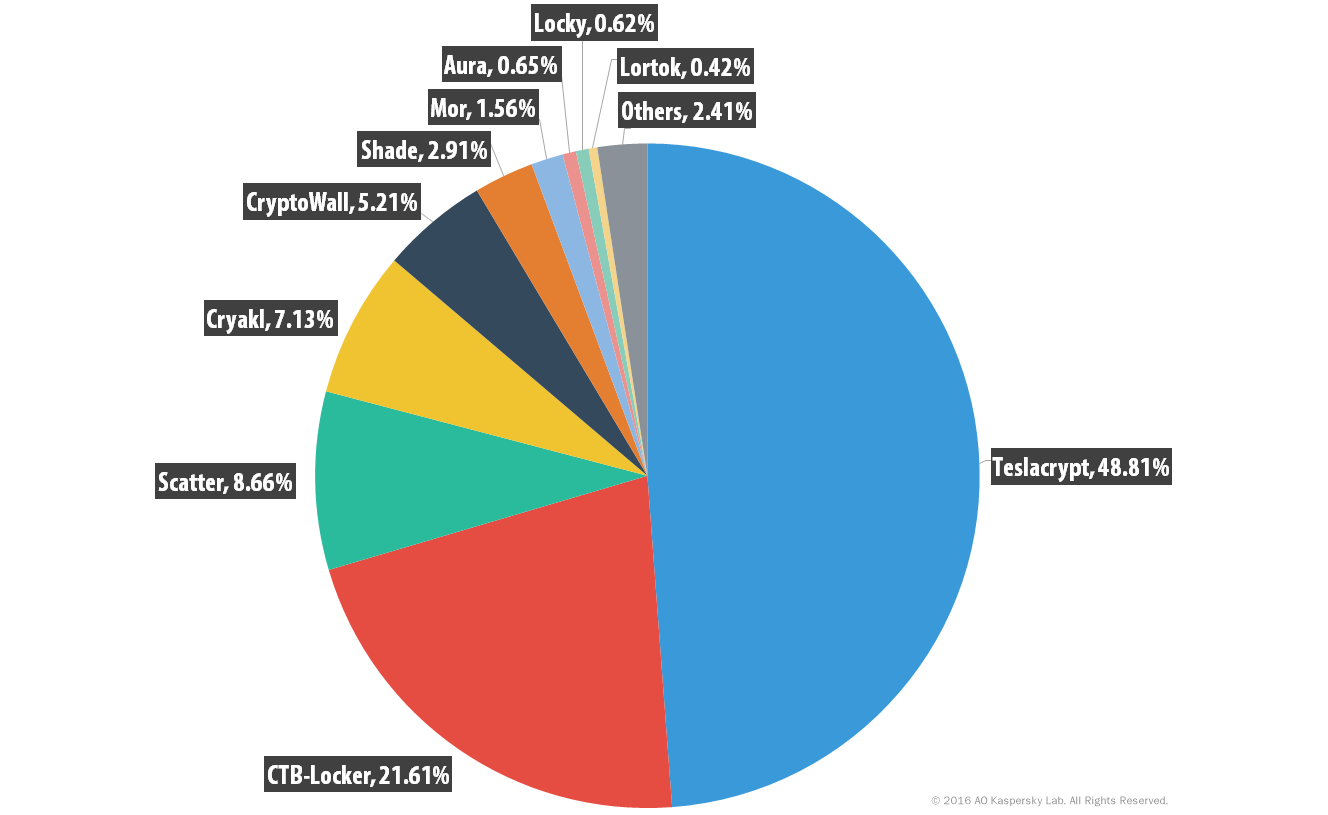

By 2015, multiple variants impacting multiple platforms were wreaking havoc on users around the world. Kaspersky’s SecureList reports that from April 2014 to March 2015, the most prominent ransomware threats were CryptoWall, Cryakl, Scatter, Mor, CTB-Locker, TorrentLocker, Fury, Lortok, Aura, and Shade. “Between them they were able to attack 101,568 users around the world, accounting for 77.48% of all users attacked with crypto-ransomware during the period,” the report states. In just one year, the landscape shifted significantly. According to Kaspersky’s 2015-2016 research, “TeslaCrypt, together with CTB-Locker, Scatter and Cryakl were responsible for attacks against 79.21% of those who encountered any crypto-ransomware.”

Percentage distribution of ransomware variants observed by Kaspersky Labs, 2015-2016. Image originally taken from SecureList.

The Biggest Ransomware Attacks and Most Prominent Variants

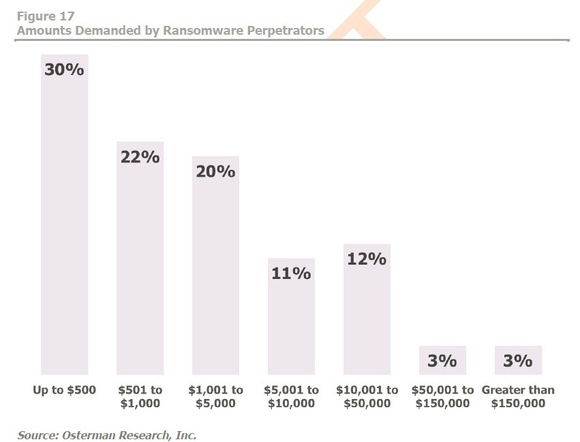

Given the advancement of ransomware and attack campaigns, it’s not surprising that the biggest ransomware attacks have occurred in recent years. Ransom demands are also on the rise. Reports indicate that average demands hovered around $300 in the mid-2000s, but are averaging around $500 today. Usually, a deadline is assigned for payment, and if the deadline passes, the ransom demand doubles or files are destroyed or permanently locked.

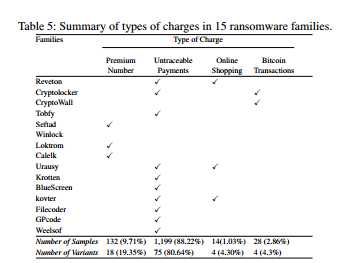

Ransom charges across 15 major ransomware families. Image via Northeastern University.

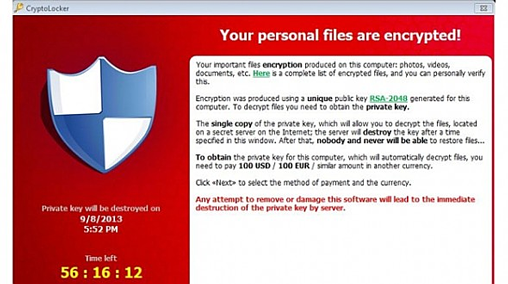

CryptoLocker was one of the most profitable ransomware strains of its time. Between September and December 2013, CryptoLocker infected more than 250,000 systems. It earned more than $3 million for its creators before the Gameover ZeuS botnet, which was used to carry out the attacks, was taken offline in 2014 in an international operation.

Subsequently, its encryption model was analyzed, and there is now a tool available online to recover encrypted files compromised by CryptoLocker. Unfortunately, CryptoLocker’s demise only led to the emergence of several imitation ransomware variants, including the commonly known clones CryptoWall and TorrentLocker. Gameover ZeuS itself re-emerged in 2014, “in the form of an evolved campaign sending out malicious spam messages.” Since that time, there has been a steady uprising in the number of variants and attacks, with primary high-value targets in the banking, healthcare, and government sectors.

A CryptoLocker ransom message. Image via Computer World.

From April 2014 through early 2016, CryptoWall was among the most commonly used ransomware varieties, with various forms of the ransomware targeting hundreds of thousands of individuals and businesses. By mid-2015, CryptoWall had extorted over $18 million from victims, prompting the FBI to release an advisory on the threat.

In 2015, a ransomware variety known as TeslaCrypt or Alpha Crypt hit 163 victims, netting $76,522 for the attackers behind it. TeslaCrypt usually demanded ransoms by Bitcoin, though in some cases PayPal or My Cash cards were used. The ransom amounts ranged from $150 to as much as $1,000.

Also in 2015, a group known as the Armada Collective carried out a string of attacks against Greek banks. “By targeting these three Greek financial institutions and encrypting important files, they hope to persuade the banks into paying the sum of €7m each. It goes without saying that, being able to pull three different types of attack over the course of five days, is quite worrying regarding bank security,” reported Digital Money Times. The attackers demanded a ransom of 20,000 bitcoin (€7m) from each bank, but instead of paying it, the banks ramped up their defenses and avoided further disruptions in service, despite subsequent attempts by Armada.

For attacks against larger companies, ransoms have been reported to be as high to $50,000, though a ransomware attack last year against a Los Angeles hospital system, Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center (HPMC), allegedly demanded a ransom of $3.4 million. The attack forced the hospital back into the pre-computing era, blocking access to the company’s network, email, and crucial patient data for ten days.

Ultimately, the company only paid $17,000 to regain access to its critical data after being blocked from essential computer systems and communications services. An update from HPMC indicates that the initial reports of a ransom demand of $3.4 million were inaccurate, and that the hospital paid the requested $17,000 (or 40 Bitcoins at the time) in order to quickly and efficiently restore operations. A little over one week later, the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services was infected with a program that blocked the organization’s access to its data. However, the that the agency successfully isolated infected devices and did not pay the ransom.

In March 2016, Ottawa Hospital was hit by ransomware that impacted more than 9,800 machines – but the hospital responded by wiping the drives. Thanks to diligent backup and recovery processes, the hospital was able to beat attackers at their own game and avoid paying ransom.

That same month, Kentucky Methodist Hospital, Chino Valley Medical Center, and Desert Valley Hospital in California were hit by ransomware. “Kentucky Methodist Hospital information systems director Jamie Reid named the malware involved as Locky, a new bug that encrypts files, documents and images and renames them with the extension .locky,” reports BBC.com noting that none of the hospitals impacted were believed to have paid the ransom. After discovering the attack on March 18, 2016, most systems were restored by March 24 and no patient data was compromised. However, the attack also caused disruptions at several other hospitals, as shared systems were taken offline.

March 2016 also saw the appearance of the Petya ransomware variant. Petya is an advanced ransomware that encrypts a computer’s master file table and replaces the master boot record with a ransom note, rendering the computer unusable unless the ransom is paid. By May, it had further evolved to include direct file encryption capabilities as a failsafe. Petya was also among the first ransomware variants to be offered as part of a ransomware-as-a-service operation.

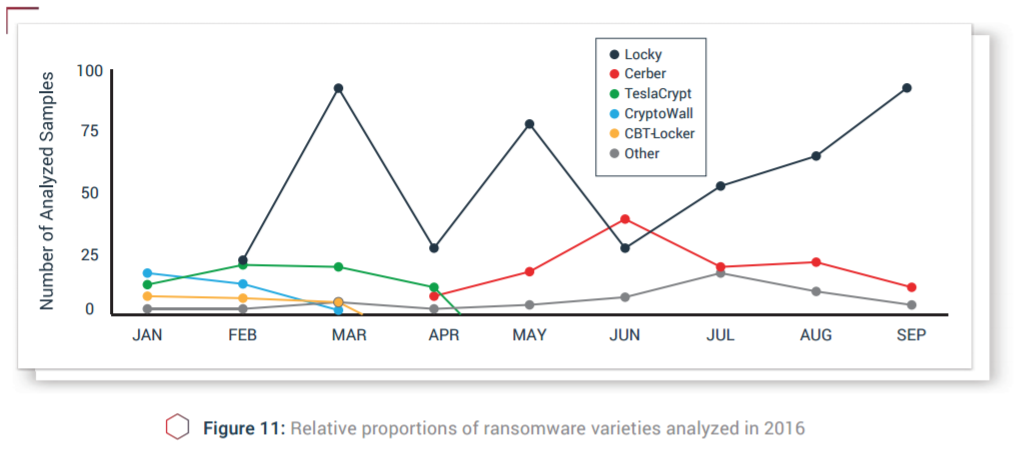

In a May 2016 article, ZDNet reported “According to detections by Kaspersky Lab researchers, the top three ransomware families during the first quarter of the year were: Teslacrypt (58.4 percent), CTB-Locker (23.5 percent), and Cryptowall (3.4 percent). All three of these mainly infected users through spam emails with malicious attachments or links to infected web pages.”

By mid-2016, Locky had cemented its place as one of the most commonly used ransomware varieties, with PhishMe research reporting that Locky use had outpaced CryptoWall as early as February 2016.

Breakdown of ransomware variants observed by PhishMe from January-September 2016. Image via PhishMe.

On Black Friday (November 25) of 2016, the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency fell victim to a ransomware attack that disrupted train ticketing and bus management systems. Attackers demanded a whopping 100 Bitcoin ransom (equivalent to about $73,000 at the time), but thanks to speedy response and comprehensive backup processes, the SFMTA was able to restore its systems within two days. Despite not having to pay the ransom, there were still some costs borne by the SFMTA, as passengers were able to ride without paying fares during the two-day period that systems were down. The ransomware used in the attack is believed to have been Mamba or HDDCryptor.

One of the first ransomware variants to target Apple OS X also emerged in 2016. KeRanger mostly impacted users utilizing the Transmission application but affected about 6,500 computers within a day and a half. KeRanger was swiftly removed from Transmission the day after it was discovered.

2016 was a major year for ransomware attacks, with reports from early 2017 estimating that ransomware netted cybercriminals a total of $1 billion.

The Future of Ransomware

These incidents are catapulting ransomware into a new era, one in which cybercriminals can easily replicate smaller attacks and carry them out against much larger corporations to demand larger ransom sums. While some victims are able to mitigate attacks and restore their files or systems without paying ransoms, it takes only a small percentage of attacks succeeding to produce substantial revenue – and incentive – for cybercriminals.

A breakdown of ransom amounts demanded by attackers. Image via Osterman Research/Network World.

Even paying a ransom doesn’t guarantee that you’ll be granted access to your files. The CryptoLocker ransomware “extorted $3 million from users but didn't decrypt the files of everyone who paid,” CNET reports, based on findings from an article in the Security Ledger. A survey from Datto found attackers neglected to unlock victims’ data in one out of every four incidents where ransoms were paid.

Ransomware operations continue to get more creative in monetizing their efforts, with Petya and Cerber ransomware pioneering ransomware-as-a-service schemes. The authors of Cerber were especially opportunistic, offering their ransomware operations as a service in return for a 40% cut of the profits earned from paid ransoms. According to Check Point researchers, Cerber infected 150,000 victims in July 2016 alone, earning an estimated $195,000 – of which $78,000 went to the ransomware’s authors.

The potential for profit for ransomware authors and operators also drives rapid innovation and cutthroat competition amongst cybercriminals. ZDNet recently reported on the PetrWrap ransomware, which is built with using cracked code lifted from Petya. For victims, the source of the code does not matter – whether you are infected with Petya or PetrWrap, the end result is the same: your files are encrypted with an algorithm so strong that no decryption tools currently exist.

What’s next for ransomware? A new report from the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) and National Crime Agency (NCA), as reported in a ZDNet article, warns of developing threats such as ransomware-as-a-service and mobile ransomware

In addition, 2017 saw the first reported ransomware attack on connected devices. According to The Guardian, 55 traffic cameras were infected with the WannaCry ransomware. While this attack amounted to little damage, all Internet of Things (IoT) devices (such as smart TVs, fitness trackers, etc.) are vulnerable. The rate at which the IoT is growing, combined with the widely-reported insecurity of IoT devices, provides a whole new frontier for ransomware operators.

Best practices for ransomware protection, like regular backups and keeping software up-to-date, do not apply to most connected devices, and many IoT manufacturers are sluggish or simply negligent when it comes to releasing software patches. As businesses become increasingly reliant on IoT devices to run operations, a spike in ransomware attacks on connected devices may occur.

Critical infrastructure poses another troubling target for future ransomware attacks, with DHS enterprise performance management office director Neil Jenkins warning at the 2017 RSA Conference that water utilities and similar infrastructure could make for viable, high-value targets for attackers. Jenkins referenced a January 2017 ransomware attack that temporarily disabled components of an Austrian hotel’s keycard system as a potential predecessor for more significant attacks on infrastructure to come.

Protecting Against Ransomware Attacks

There are steps that end users and companies alike can take to significantly reduce the risk of falling victim to ransomware. As referenced above, following fundamental cybersecurity best practices are key to minimizing the damage of ransomware. Here are four vital security practices to have in any business:

- Frequent, Tested Backups: Backing up every vital file and system is one of the strongest defenses against ransomware. All data can be restored to a previous save point. Backup files should be tested to ensure data is complete and not corrupted.

- Structured, Regular Updates: Most software used by businesses is regularly updated by the software creator. These updates can include patches to make the software more secure against known threats. Every company should designate an employee to update software. Fewer people involved with updating the system means fewer potential attack vectors for criminals.

- Sensible Restrictions: Certain limitations should be placed on employees and contractors who:

- Work with devices that contain company files, records and/or programs

- Use devices attached to company networks that could be made vulnerable

- Are third-party or temporary workers

- Proper Credential Tracking: Any employee, contractor, and person who is given access to systems create a potential vulnerability point for ransomware. Turnover, failure to update passwords, and improper restrictions can make result in even higher probabilities of attack at these points.

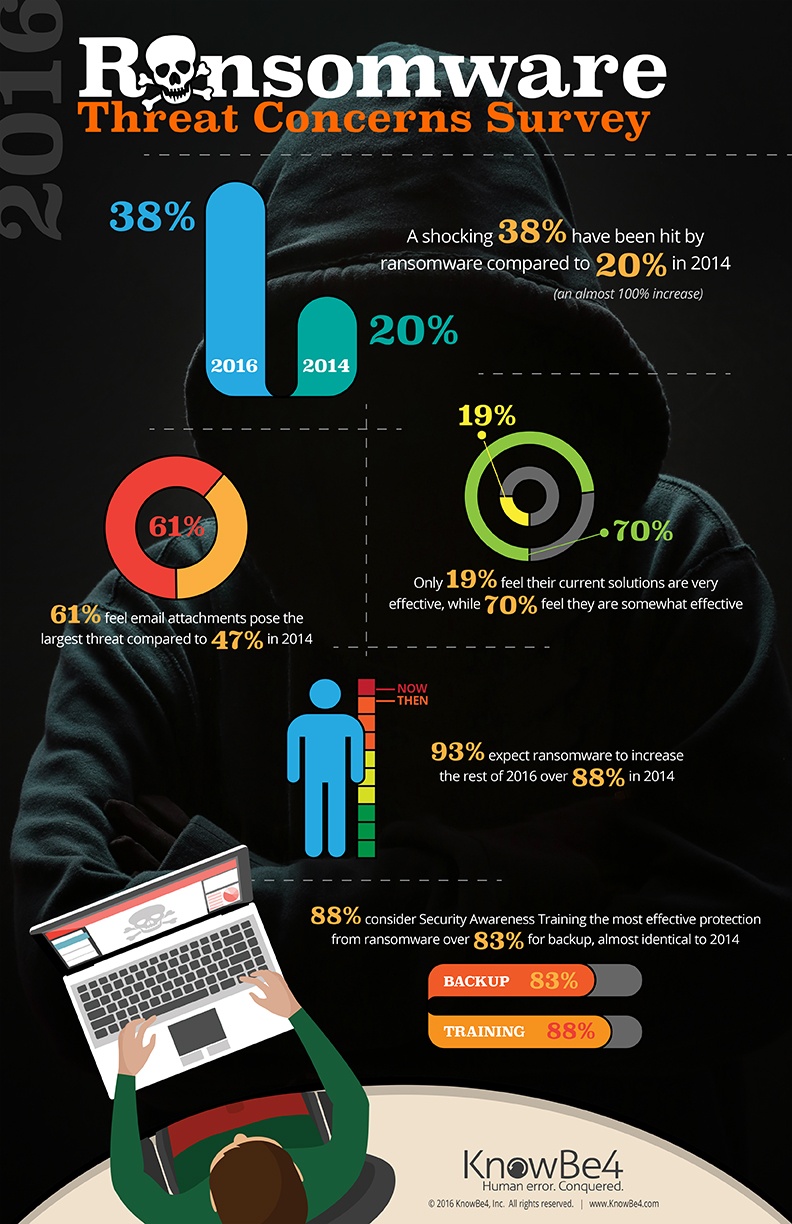

An infographic on ransomware concerns from KnowBe4 aims to highlight the need for end user education in ransomware protection.

Despite these best practices being fairly well-known, many individuals fail to regularly backup their data, and some enterprises do so only within their own networks, meaning that backups can be compromised by a single ransomware attack.

Effective ransomware defense ultimately hinges on education. Users and businesses should take time to learn about their best options for automated data backups and software updates. Education on the telltale signs of ransomware distribution tactics, such as phishing attacks, drive-by downloads, and spoofed websites, should be a top priority for anyone using an connected device today.

Businesses should also implement security solutions that enable advanced threat protection. Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) tools monitor activities on endpoints and networks to identify and mitigate threats. Digital Guardian offers Endpoint Detection and Response capabilities that can help you prevent ransomware from affecting your business. Our ability to detect and block advanced threats across the entire attack lifecycle allowed us to successfully detect and contain WannaCry for all our advanced threat protection customers. Learn more about our EDR capabilities and see why DG was ranked as a leader in the 2018 Forrester Wave for EDR.

Further Reading on Ransomware and Ransomware Attacks:

- Cutting the Gordian Knot: A Look Under the Hood of Ransomware Attacks

- Ransomware in the Wild: It’s an Emergency

- Ransomware Rising – Criakl, OSX, and others – PhishMe Tracks Down Hackers, Identifies Them and Provides Timeline of Internet Activities

- Self-propagating ransomware spreading in the wild

- A Short History & Evolution of Ransomware

- The rise of Android ransomware

- Easy, Cheap, and Costly: Ransomware is Growing Exponentially

- New Locky variant – Zepto Ransomware Appears On The Scene

- A closer look at the Locky ransomware

- CryptoLock (and Drop It): Stopping Ransomware Attacks on User Data

- Ransomware Statistics – Growth of Ransomware in 2016

- Ransomware: A Highly-Profitable Evolving Threat

- 93% of phishing emails are now ransomware

- The cost of ransomware attacks: $1 billion this year

- Hacker Lexicon: A Guide to Ransomware, the Scary Hack That’s on the Rise

- The Growing Threat of Ransomware

- OK, panic—newly evolved ransomware is bad news for everyone

Looking to learn more about Fortra's Digital Guardian?

Have a question about data loss prevention, secure collaboration, or SaaS data protection? Don't hesitate to get in touch. We're here to help.