Attackers who peddle ransomware have been raking in the money over the last several months, almost a third more than what they made the previous quarter.

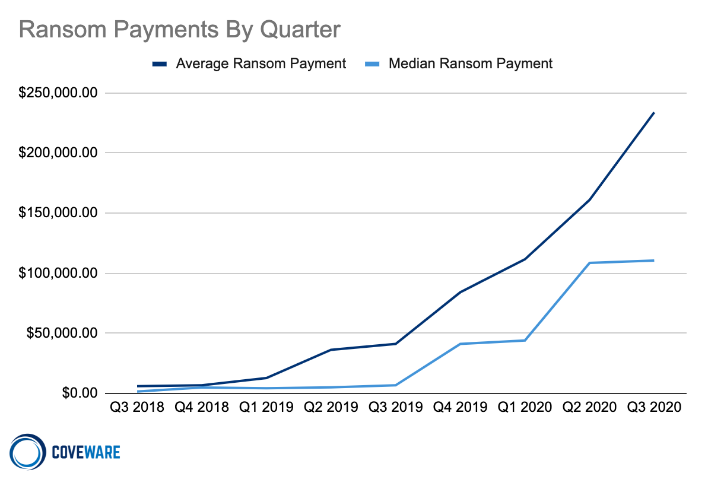

According to recent reports, the average ransom payment surged to $233.817 in Q3 this year, up 31% from Q2.

Attackers aren't necessarily getting smarter, nor is the actual ransomware getting more sophisticated. Instead it seems as if it's a combination of things, including attackers discovering they can scale techniques to target larger enterprises, an increase in employees working from home - in turn exposing them to risk, more employees using Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) and other vulnerable technologies that have opened the door. That’s at least according to trends observed by Coveware, a firm that aggregates global ransomware and cyber extortion data.

“The biggest change over the past 6 quarters is threat actors now realize that their tactics scale to much larger enterprises without much of an increase in their own operating costs. The profit margins are extremely high and the risk is low,” the company wrote in a summary of Q3 ransomware activity this week. “This problem will continue to get worse until pressure is applied to the unit economics of this illicit industry.”

We saw earlier this year how the emerging distributed workforce helped contribute to data loss at many enterprises. Having employees work from home, where they may let their guard down more than they would at work, use personal devices more often, and not always use a VPN, can open the door to ransomware attacks as well.

While the median ransomware payment ($110,532) has plateaued a bit, the average ransom payment shows no sign of slowing down, at least according to the company’s chart that maps ransom payments by quarter.

Sodinokibi aka REvil, which commanded headlines much of the summer, controlled much of the market share of attacks, according to the firm, with Maze, since shuttered, taking second place.

It will be interesting to see what kind of market share Ryuk, a strain of ransomware that had been fairly quiet since, at least since the beginning of 2020, fetches in the Q4 version of Coveware's report. The ransomware, tied to a campaign of Trickbot infections, has spawned a wave of targeted attacks, mostly on hospitals and the healthcare industry, the past two weeks.

In addition to the heightened average ransom payment, another big shift the firm has observed is around threats to exfiltrate data. Almost 50% of ransomware cases it saw in Q3 included a threat to release exfiltrated data with encrypted data. That’s double the amount it saw in Q2.

This of course is an alarming trend and something that’s forced some victim companies to engage with attackers even if they’d have no reason to otherwise, for instance, if they have backups in place. Of course, as is the case with anything involving a ransomware attacker, there's no honor among thieves. It's no guarantee the attacker won't release the data anyways, or failing that, ask for even more money weeks later.

As an example, the firm claims its seen Sodinokibi attackers re-extort victims weeks after the fact, and Maze attackers post data on a leak site; Conti attackers showed victims fake files but claimed they'd deleted them.

While it may help prevent brand damage, as the firm notes, "paying a threat actor not to leak stolen data provides almost no benefit to the victim."

While these attacks can be costly, the firm stresses that nothing can be as damaging for a company that's been hit as downtime. Companies hit by ransomware in Q3 experienced 19 days of downtime on average, a figure that's up 19% from the quarter preceding it.

Universal Health Services (UHS), a Fortune 500 hospital and healthcare services provider that was hit by Ryuk ransomware in September wasn't able to get itself back online for more than a month. UHS has found itself with plenty of company. Just in the last three weeks, hospitals in Vermont, New York, Oregon, Michigan, and California have experienced downtime, some for longer than a week as a repercussion of a Ryuk attack.

If they haven't already, hospitals should make efforts to ensure they're not the next victim, including having the proper mitigations in place, ensuring data is backed up, and that vulnerabilities are patched.

Looking to learn more about Fortra's Digital Guardian?

Have a question about data loss prevention, secure collaboration, or SaaS data protection? Don't hesitate to get in touch. We're here to help.